There was a time when a diary that you wrote in long hand, in India ink, kept confidential in a false drawer in your worn mahogany desk, was private, and safe from the prying eyes of anyone including our government – as a matter of law.

Not so anymore.

I advise my clients these days to destroy their mental notes.

From the vantage of a criminal defense lawyer (and “recovering” federal and state prosecutor), I’ve seen the most craven governmental intrusions into individual privacy – shocking to any Accused person who never before had to endure the unwanted embrace of a criminal prosecution.

Here in Loudoun County, if you’re arrested and denied bail, when you are jailed in Loudoun’s Adult Detention Center (ADC), don’t make the mistake of talking about your case on the jail house phone with your wife (or anyone else), because everything you say is taped – and they’ll use it against you.

We have an “expectation” of what is private, predicated upon our 4th Amendment right to be secure in our person and property, and the penumbra of other constitutional rights. This is what must be protected.

Who would expect it was right and just to intercept a family conversation when the Accused has no other way to talk to his family?

We believe we get to control what information is circulated about ourselves – in or out of jail.

But practice and the law is more complicated than what we might fairly expect and what common sense dictates.

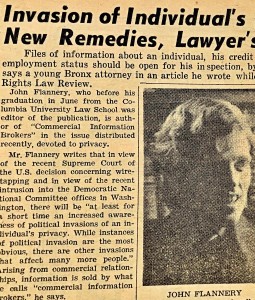

When I was a puppy law student, I was concerned with privacy, so much so that I wrote about it for our journal, the Columbia Human Rights Law Review.

Our technology was relatively primitive in the 70’s. Indeed, I wrote how intrusions into a person’s privacy might not have been possible “if the information was manually handled and manually disseminated.”

In the 70s, Nat Hentoff said that our hardcover collection of law student essays explained “how we [could] remain free citizens and avoid the coming of what former Congressman Cornelius Gallagher [then] called ‘post-Constitutional America.’”

As kind and gracious as Mr. Hentoff’s prediction was, nothing like that happened; instead, the evolving technology has placed our constitutional guarantees at risk.

Fortunately, U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts has led the Court in recent years to identify and push back against the unrestrained warrantless use of surveillance technology.

In United States v. Jones, in 2012, the Supreme Court limited the ability of the police to use GPS devices to track a suspect, prompted by the government actually attaching such a device to a suspect’s car for 28 days. The court strongly objected that this time-stamped data opened a window not only to the suspect’s particular movements but also his “familial, political, professional, religious and sexual associations.”

In Riley v. California, in 2014, Chief Justice Roberts required a search warrant if law enforcement wanted to review the data in an Accused’s cell phone; the Chief Justice underscored the fact that “[m]odern cellphones are not just another technological convenience… They could just as easily be called cameras, video players, Rolodexes, calendars, tape recorders, diaries, albums, televisions, maps or newspapers.”

Only days ago, in 2018, in Carpenter v. United States, Chief Justice Roberts again, writing for the majority in a 5-4 decision, in another dramatic look at digital privacy, renounced the government’s collection of location information from a cell phone company without a warrant.

It was especially intrusive, the Court found, when the data was collected for over 127 days at 12,898 locations without a search warrant.

We have hope that the Court will preserve individual privacy when other cases must consider, say, the government’s access to the purchases we make, the websites we visit, the shows we watch, the persons we contact, and that these circumstances shall require a search warrant.

We have another significant challenge. We have had several cases where government protocols to respect the confidentiality of journalists’ sources have been disregarded and tech tools have made warrantless intercepts of a journalists’ information to identify or confirm sources and their dates of contact. This is not yet before the Court. But it really should be.

This misconduct begs the questions under the First Amendment whether the government seeks to chill the reporters’ privilege to maintain a source as confidential and frustrate the reporters’ efforts to make transparent to the public what our government may be hiding.