I’m a recovering N.Y. federal prosecutor.

I say “recovering” because you never quite get over the power and authority you enjoyed as a young man – as a ‘puppy” prosecutor.

In New York, a port city, the cases are a big deal, mobsters plot their crimes a few blocks from the U.S. Attorney’s Office in lower Manhattan, vast quantities of drugs, heroin and cocaine come into the Big Apple from every direction imaginable, there are illegal transfers of money, in and out of banks, securities fraud and oceans of bad acts and words deceiving the public, plots and devices hatched by a variety of rogues within walking distance of Foley Square, where the Courts and federal prosecutors are lodged.

If you do it right, when you’re a prosecutor, no matter the jurisdiction, your mission is to do justice for the individuals charged.

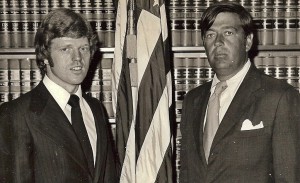

The Executive US Attorney for the Southern District of New York, Sylvio J. Mollo, pulled the flag around him while he was testing my resolve to become an Assistant U.S. Attorney.

Sylvio said, “when you stand before the court as an Assistant U.S. Attorney, you represent the people and the government, but, like the flag [that he had in his hand], those you represent are silent, not there with you, and they depend on you to do what’s right.”

Years after walking out of my last grand jury as a prosecutor, I started representing the Accused, upset about how the government was pushing around those they accused – in a way I’d been instructed was just plain wrong. Continue reading